What's the difference between an artist and a creator?

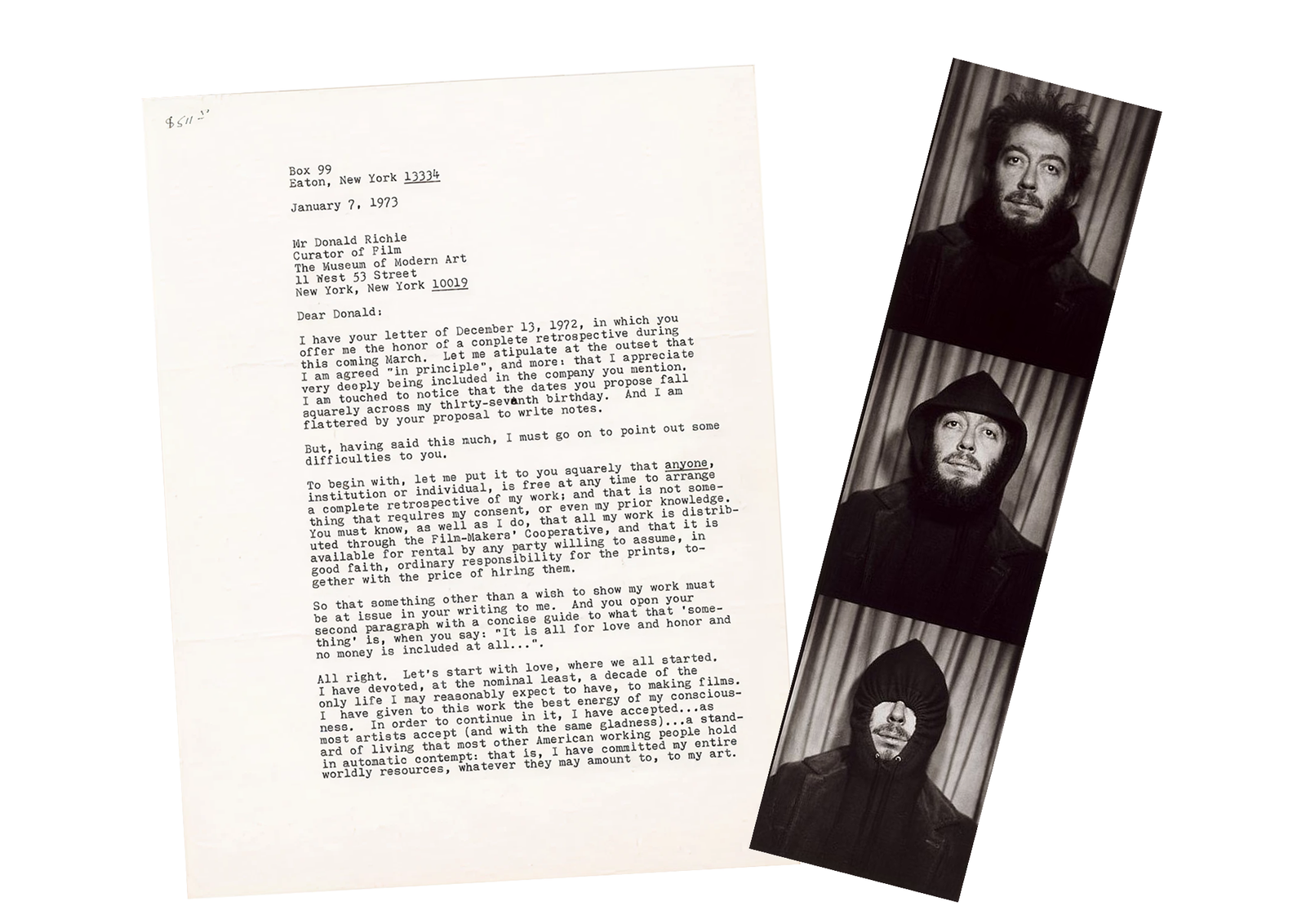

In 1973, experimental filmmaker Hollis Frampton wrote a letter to MoMA that captures a paradox that still defines creative work today.

The Museum of Modern Art had offered the filmmaker a retrospective of his work. However he was also told there would be "no money included at all" and it would be "all for love and honor” instead.

Frampton was furious, and responded with a lengthy letter listing all the people who would be paid for the show but not him: projectionists, security guards, administrators, film developers, on and on. Why was everyone but the artist being compensated?

"I, in my singular person, by making this work, have already generated wealth for scores of people," Frampton wrote. "Ask yourself whether my lab would print my work for 'love and honor.' They would explain to me, ever so gently, that human beings expect compensation for their work. Yet while all these others are to be paid for their part in a show that could not have taken place without me, I, the artist, am not to be paid."

Frampton’s plea is both specific to his circumstances and universal for artists everywhere. (There’s no record of the curator’s response, but the show did happen.)

But this isn’t always how things work out, as we find when we fast forward three decades to a very different moment in the history of creative compensation.

It’s 2004. An artist named David Choe gets asked to paint a mural in the office of a young startup looking to decorate their walls in Northern California. Because it’s Silicon Valley and they specifically wanted Choe, he gets offered a choice of compensation: $60,000 in cash or the equivalent in company stock.

Choe chose the stock.

The startup was Facebook.

When the company went public a few years later, those shares were worth more than $200 million. Making it almost certainly the best-paying mural gig in history.

Divergent paths

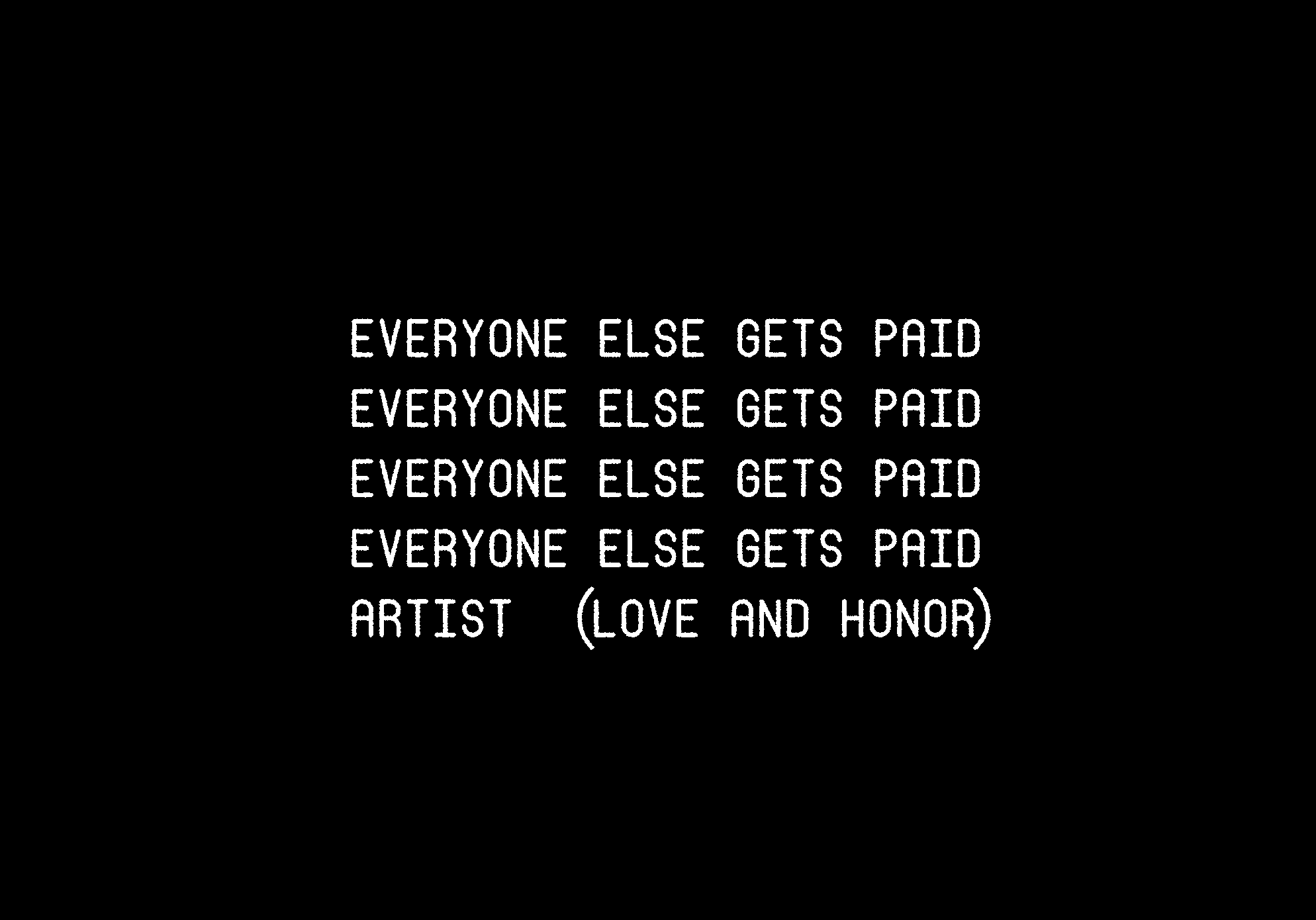

These two stories represent extreme poles of how we do and don't value creative work. Creative work done for artistic purposes is thought to exist for reasons above money. "Love and honor” is a convenient excuse to not compensate for it, “exposure” too. Creative work for commercial purposes, on the other hand, can be handsomely rewarded. However you’re doing a job for somebody else.

The people who make the first kind of work are historically called “fine artists.” The people who make the second kind of work are called “commercial artists.” These two roles defined the creative landscape for centuries. There’s work you do for yourself (capital-A Art) and there’s work you do for others (sometimes Art, but also decoration, ego-fluffing, and market-driven motivations). Most creative people straddle a hybrid of both: commercial art for their livelihoods, fine art for their souls.

(This post implicitly uses visual artists as the representative category of what an “artist” is, but the logic and term equally apply to other types: writers, filmmakers, musicians, performing artists, so on.)

In recent decades a similar but distinct creative role has emerged: the creator. People who make a living from subscriptions, crowdfunding, selling merch, and other forms of direct exchange unlocked by the web.

Like artists, creators have a lot of freedom in what they do. They’re even more free in some ways, as they aren’t confined to the canon of what they’re “supposed to do.” All tools of the market are at their disposal: from products to livestreams to memecoins to ghost kitchens to limited edition drops. Unlike artists, they don't have to navigate the academy system or art world politics to do it.

Creators don’t answer to a boss, but they do answer to an audience. For most this is a smaller audience than they hope. For a few this means fame and attention beyond imagination whose pressure can create a performative cycle that can eventually lead to burnout and debilitating narcissism.

Also unlike artists, creators are explicitly commercial in what they do. They want you to smash that like and subscribe button. They launch courses and new products to further monetize themselves. They see their work as inherently commercial, even industrial. The opposite is true for most artists.

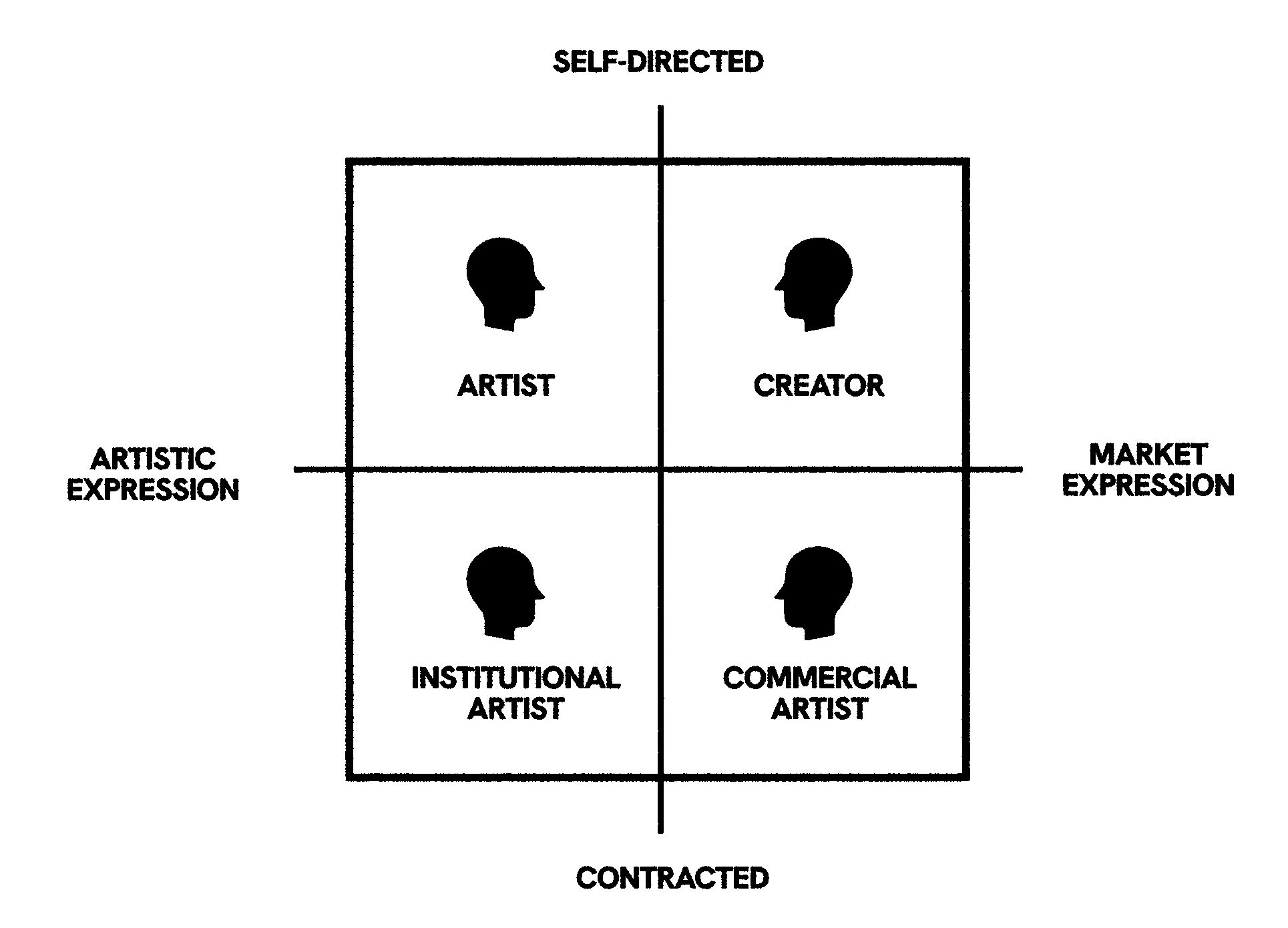

Artists, commercial artists, and creators

If we think about the functions each of these roles perform at a high level, we get a sense of the differences between them.

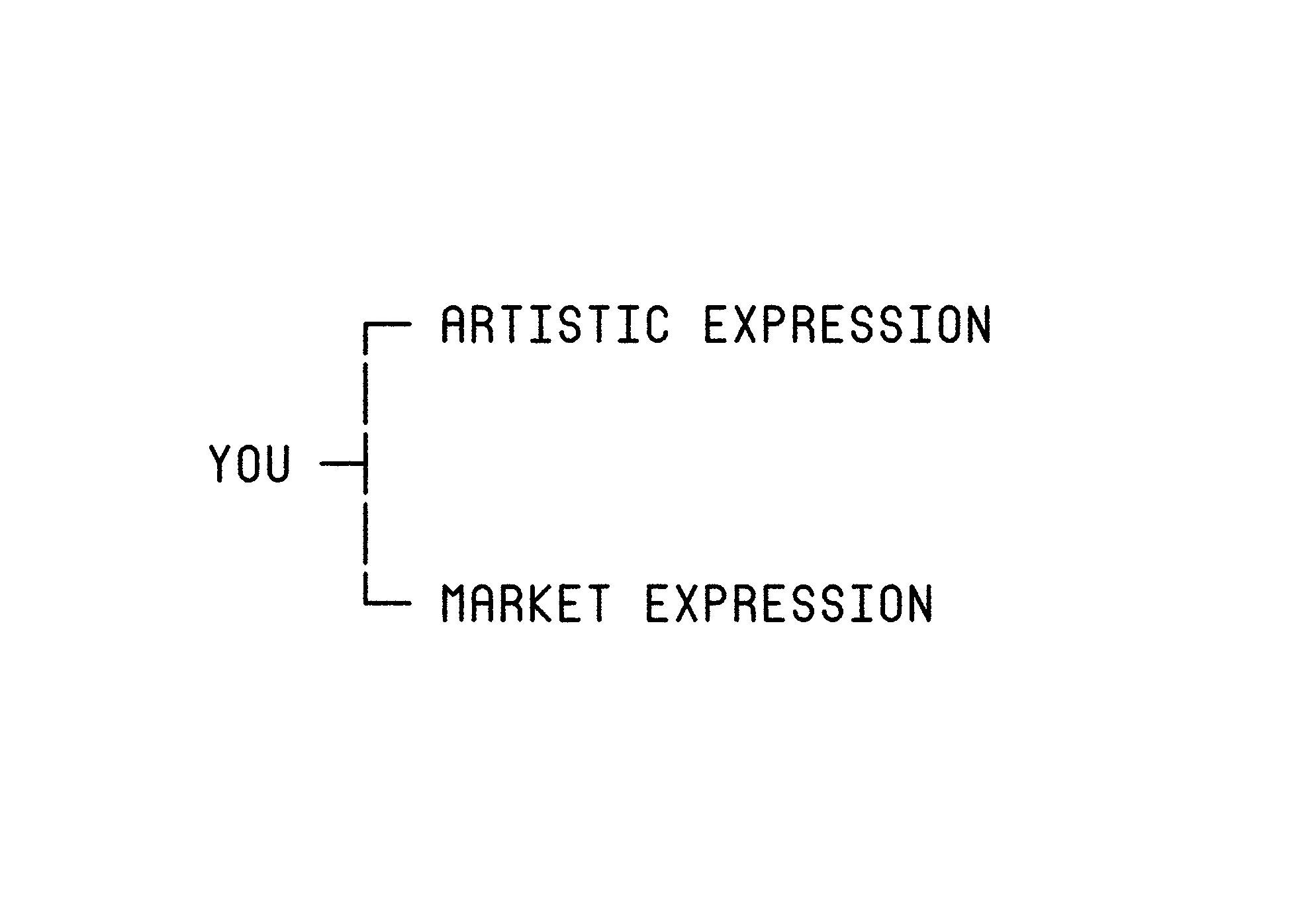

An artist is a self-directed artistic expressor. They work for themselves and express what they want. There’s no one beyond their anxiety looking over their shoulder telling them what to do.

A creator is a self-directed market expressor. Everything they do has a commercial aim at its core, but they answer to themselves and their audience. Rather than a traditional boss, they have an algorithmic one that implicitly and explicitly shapes their output.

A commercial artist, or "a creative," is a contracted market expressor. Everyone who works at an ad agency or as an in-house designer fits into this bucket. This group is much better paid than anyone else because they fulfill a market-oriented purpose. Today this role is often called a “creative” — a dehumanizing phrase with roots in the advertising industry.

An institutional artist is a form of contracted artistic expression. Think of an artist being asked to produce a Biennale commission or a piece for a museum. They are being contracted for their voice in a defined way. You have to have “made it" to be part of this quadrant.

These segments also show us how and by whom each gets paid:

Role: Artist

Who pays: Patrons, foundations, collectors

How: Grants, residencies, commissions, sales of work

Role: Creator

Who pays: Audiences, platforms, sponsors

How: Memberships, merch sales, rev shares, sponsorships

Role: Institutional artist

Who pays: Museums, public arts, universities, nonprofits

How: Commissions, grants, honoraria, stipends, exhibition fees

Role: Commercial artist or Creative

Who pays: Employers, agencies, brand clients

How: Salaries, day rates, project fees, retainers

The artist is the least compensated because there’s no outside entity contracting them to produce their work. Commercial artists and creatives are the highest paid because there are. Creator incomes range across a huge curve defined by the size of the internet. Institutional artist funds are the hardest and often stingiest to get.

In terms of artist compensation, the data supports this. Art critic Ben Davis reports in his excellent book 9.5 Theses On Art and Class that “artists earn less than workers in their reference occupational category (professional, technical and kindred workers), whose members have comparable human capital characteristics (education, training and age).”

Artists get paid less than people like them. Now we see why.

How big are these groups?

How many people are in each quadrant?

Ben Davis writes that of the 2.1 million self-declared artists in the US Census in 2010, “fewer than one in ten were ‘fine artists.’ About 10% of these so-called creative laborers worked in architecture and about 17% in the performing arts. By far the largest portion of creative laborers — close to 40% — were classified as ‘designers’ of various kinds.”

This suggests the number of artists is quite small, at least when it comes to full-on careers. But more recent data suggests a more nuanced picture. In a 2023 survey, 48% of Americans reported having an active creative practice — art, music, or writing. This makes creative expression as popular as watching the NFL — long considered the most American thing there is. These numbers are likely to grow. Among Gen Alpha, 30% report that their goal in life is to be a creator.

These numbers also mean that most people really do it for “love and honor” (sorry Hollis Frampton) rather than money. Some intentionally because they’re making for themselves. Others because they don't yet have an audience that will reward them, and likely never will.

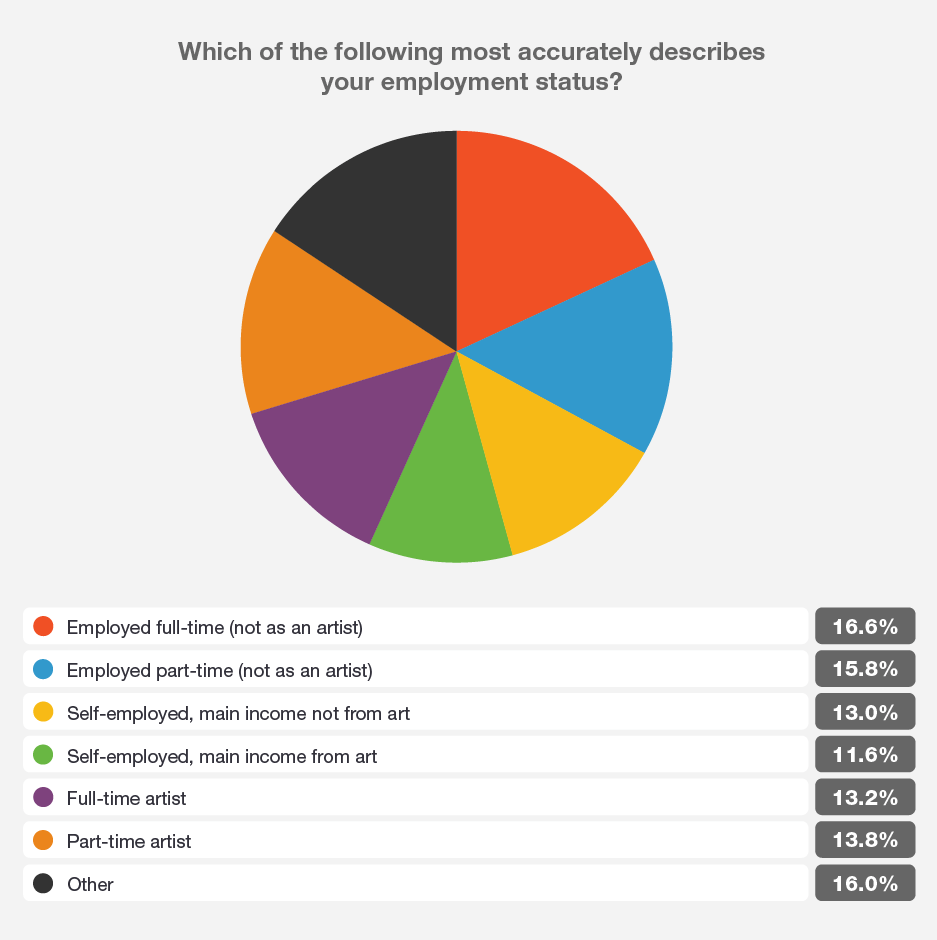

If we dig deeper into just the segment of artists who already generate income from their work, we get a better sense of the dynamics. A 2022 survey by the Saatchi gallery of 500 artists who make money from their art lets us do exactly that. Their report found that 13% of artists were able to earn a full-time living from their work, while 16% were employed full-time in non-art jobs.

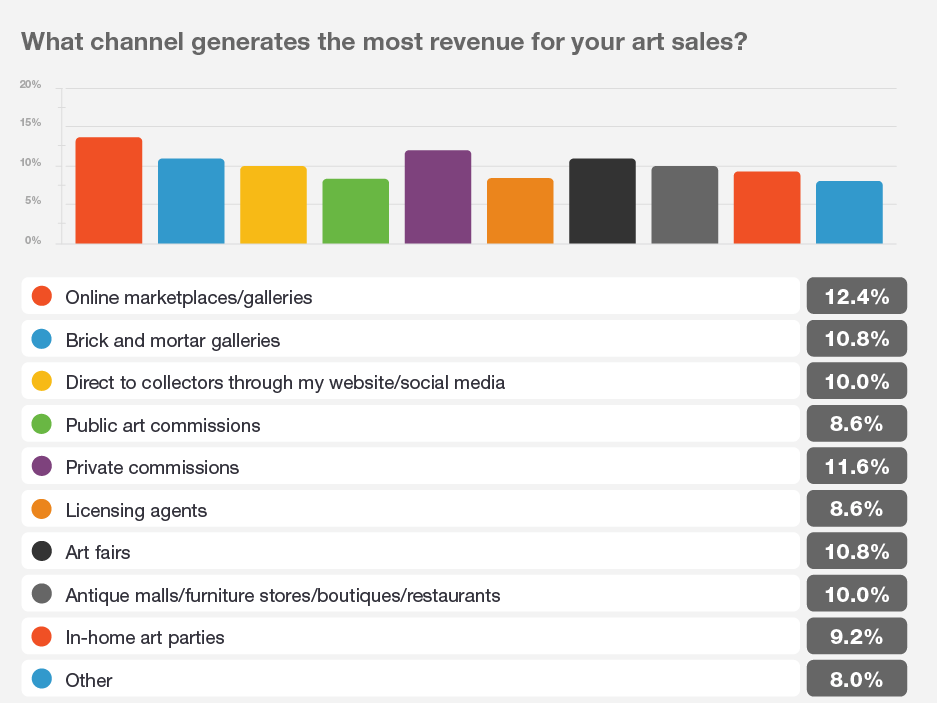

Most of the artists have to piece together an income from various sources. A minority do not. The same survey also asked artists their sources of funding, which reveals the creative funding complex the four quadrants listed.

The need for new models

Contrasting Frampton's MoMA letter with Choe's Facebook windfall and today's creator economy reveals persistent patterns in how creative work is valued. And how it isn’t.

Creative work by inspiration is seen as unpaid and without value. Creative work for commercial purposes is worth compensation if it meets the brief. Institutions remain the primary mediators of payment, whether they're museums, corporations, or technology platforms. Virtually all who participate move through them in one form or another.

What, if anything, about this structure can and should change? We feel drawn to two ideas that feel deeply intertwined:

1) Increasing creative agency

2) Increasing economic control

By increasing creative agency, we mean freedom for creative people to move between quadrants. Artist, Creator, Institutional Artist, and Commercial Artist are all potentially attractive and consequential roles for a creative person to embody, depending on the context. We should continue to work towards a creative universe where these roles are fluid and open to all. We should also grow the respect for the artist and creator in these contexts. As they move into market-based and contracted forms of expression, we wish to see a greater empowerment of the creative voices making the work.

By increasing economic control, we mean more direct access to funding, more sophisticated ways of using those funds, and a greater ability for the artist to determine and participate in the economic value of their work. Right now artists find themselves dependent on larger entities that translate non-commercial expression into commercial value (galleries, publishers, platforms, labels). These systems are critical, but they also have a tendency to keep artists dependent, financially precarious, and have historically imposed exploitative terms on the creators of the work. This must change.

Moving forward, not backward

Future creator-artists and artist-creators need better control of their destinies. They should be able to protect their visions, generate reliable income, and financially participate in the full outcomes of their work.

Right now this isn't easy, but this is what the Artist Corporation is designed to change. The A-Corp aims to introduce a new kind of corporate entity that can receive a wide variety of revenue sources (all areas of the quadrant); enable resource pooling (like group health insurance); and make the creation of collective ownership and shares for creative work possible for the first time.

While we feel a strong moral and romantic pull towards the solitary artist as the outsider truth-teller, we also need a structure that better organizes, values, and sustains creative work in ways that reflect all the persistent nuances of how it operates. Some things are commercial. Other things are not. Sometimes people engage in explicitly self-oriented creative projects for which no compensation makes sense. Other times it absolutely depends on it. Regardless, the people behind the work need to eat and support themselves.

These questions have plagued creative people since the beginning of time. We're just the latest in a long line of people facing this. But what if this marks the end of one era and the start of another? What if a world where it can be for love and honor and there can still be money at the end — not in every case, but in more cases than before — is actually possible?

This groupcore future is what we are actively working to manifest.