Do artists get paid for making art?

Artist Corporations are important not just as a legal structure, but as a concept that redefines creative output as real work that’s valuable and deserving of compensation.

Too often people see creative output as a frivolity, something extra that’s less valuable than “real” work. This is an attitude that’s been with us for a long time. There’s a story we often think about that vividly shows why this matters.

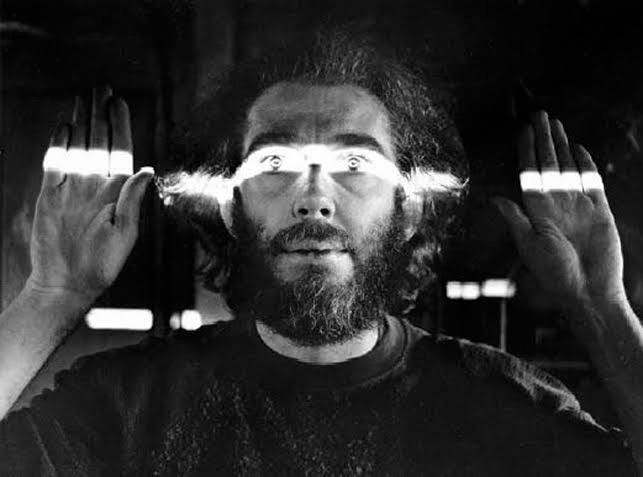

In 1973 the Museum of Modern Art offered the experimental filmmaker Hollis Frampton a retrospective — the first-ever institutional screening of avant-garde video work. The invitation from MoMA came with a catch, however: there would be “no money included.” Instead, the letter notifying Frampton of the show said it would be “all for love and honor.”

Frampton responded with a letter that explained exactly what’s wrong with this that remains deeply relevant. Here’s Hollis Frampton writing to the MoMA curator (the bold emphasis marks are his):

“Let’s start with love, where we all started. I have devoted, at the nominal least, a decade of the only life I may reasonably expect to have to making films. I have given to this work the best energy of my consciousness. In order to continue in it, I have accepted, as most artists accept (and with the same gladness), a standard of living that most other American working people hold in automatic contempt. I have committed my entire worldly resources, whatever they amount to, to my art.

“I have made the work, have commissioned it of myself, under no obligation of any sort to please anyone… But it cannot continue on love and honor alone…

“I’ll put it to you as a problem in fairness. I have made, let us say, so and so many films. That means that so and so many thousands of feet of rawstock have been expended, for which I paid the manufacturer. The processing lab was paid, by me, to develop the stuff, after it was exposed in a camera for which I paid. The lens grinders got paid. Then I edited the footage, on rewinds and a splicer for which I paid, incorporating leader and glue for which I also paid. The printing lab and the track lab were paid for their materials and services. You yourself, however meagerly, are being paid for trying to persuade me to show my work to a paying public for ‘love and honor.’ If it comes off, the projectionist will get paid. The guard at the door will be paid.

“That means that I, in my singular person, by making this work, have already generated wealth for scores of people. Multiply that by as many other working artists as you can think of…

“But it seems that, while all these others are to be paid for their part in a show that could not have taken place without me, nonetheless, I, the artist, am not to be paid. And in fact it seems that there is no way to pay an artist for his work as an artist. I have taught, lectured, written, worked as a technician… and for all those collateral activities, I have been paid, have been compensated for my work. But as an artist I have been paid only on the rarest of occasions.”

There’s no record of the curator’s reply, but Frampton’s show did happen. Perhaps arrangements were made.

But the assumption that artists should not be paid for their work and that “love and honor” should suffice is still with us. Today creative people are asked to be compensated with “exposure” and other unpaid recognition. But as Frampton’s letter points out, no other profession is expected to do this. It’s only the artist who’s asked to exist beyond money.

It’s this assumption that causes artists and creative people to be lower income than similarly educated peers. That causes them to be three-times more likely to be a gig worker than the average person. An assumption that continues to label creative output as being without monetary value, unless it’s being speculated on by wealthy people.

Can Artist Corporations immediately solve this? Doubtful. But over time, as artists and creators begin to interact with artistic and commercial institutions not just as individuals, but as legally recognized entities with real rights and economic interests, this is something that can change. Organizational power respects organizational power. We need to build some of our own.

Work creates value. Work deserves compensation. Creative work creates value. Creative work deserves compensation. Artist Corporations will help make our work and the value we create clear and worthy not of just love and honor, but payment, too.